Underwater Exploration

Hilarion Mine

The Lavrio Mines, a place of industrial development and at the same time a hell for thousands of workers. Miners daily donated their existence to the central stations of the galleries of Saint Constantine, Plaka and Keratea, carrying heavy mining tools and disappearing into the dark arcades of the Lavreotian land. Their sole purpose was the extraction of precious ores: silver, lead and later the exploitation of the derivatives from mining activity, slag. Lavrio has been a mining paradise since the ancient times. Mining activity begins as early as 3000 BC, in the arcades of Thorikos (Stoa III), where archaeologists have identified archaeological findings that attest to the presence of workers in these arcades. At that time the focus was on copper mining, for the manufacturing of tools and weapons. Thorikos is not an exaggeration to be considered the first “industrial” settlement of antiquity, since it was created to serve the needs of the workers in the arcades. Mining had gradually intensified since the 6th century BC.

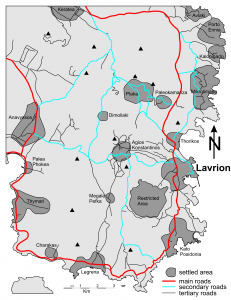

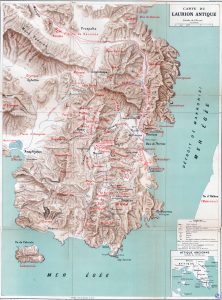

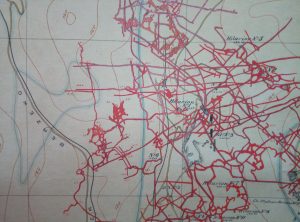

Left and Center: Map of the Lavreotiki area Right: Map of the mining concessions in the late 1880s.

Source: mindat.org

In the Classical Period (5th-4th century), at the time of the Athenian Republic, a system of cooperation was implemented, between the City of Athens and the proprietor of Lavreotiki, with businessmen for the exploitation of mines, in clear legislative terms. At the same time, slave trade and hiring of companies was developed, businesses selling food (food, water, timber), and favoured professions such as skilled craftsmen, for the construction of specialised facilities. Such facilities are located in the area of Souriza, south of the modern settlement of Agios Konstantinos, 600 meters south of the church of the Holy Trinity. A landscape of great archaeological and natural value, within the Sounio National Park, which preserves in excellent condition mineral processing laboratories, ancient laundries, furnaces, smelting laboratories etc. The extraction of silver stimulated the economy of Athens. This money funded the Parthenon construction program.

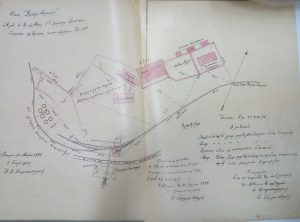

First photo on the left: Floor Plan from 1898 of the Serpieri factory. Followed by Maps of the Hilarion complex.

Photographs provided by Maria Fotiadi. Archive: Ioannis Katsikas.

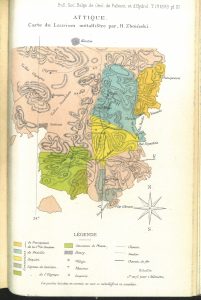

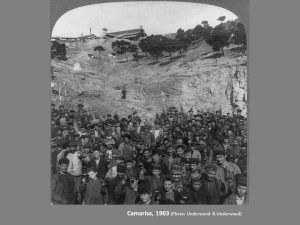

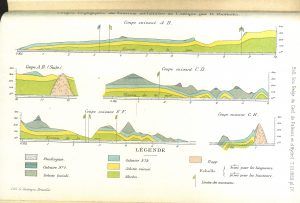

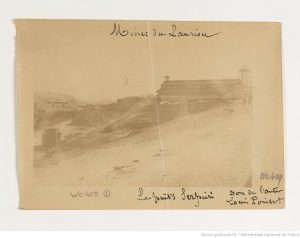

Left: Lamariza 1903 – Center: Geological sections of the metalliferous Lavrio of Attica – Right: Serpieri mine in 1894.

Sources from left to right: Lavrio Mines, Katerinopoulos Athanasios – mindat.org – Bibliothèque nationale de France.

20 July 2019

19 November 2019

24 May 2020

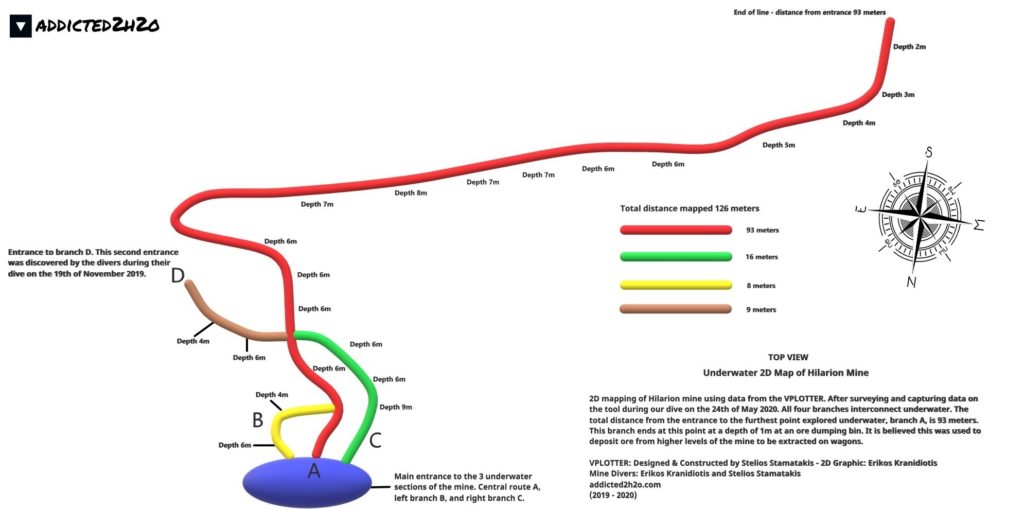

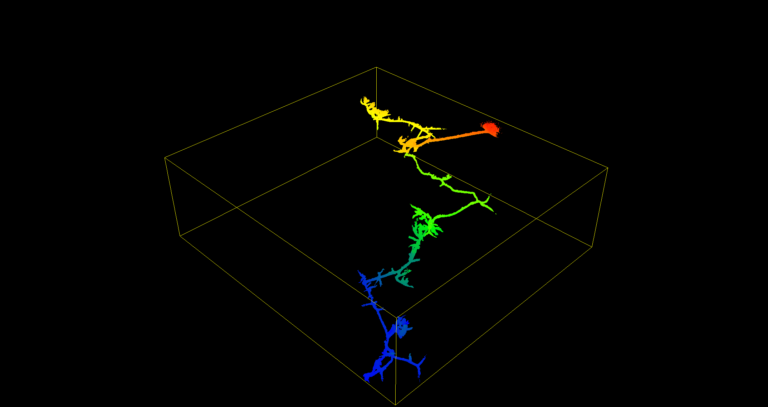

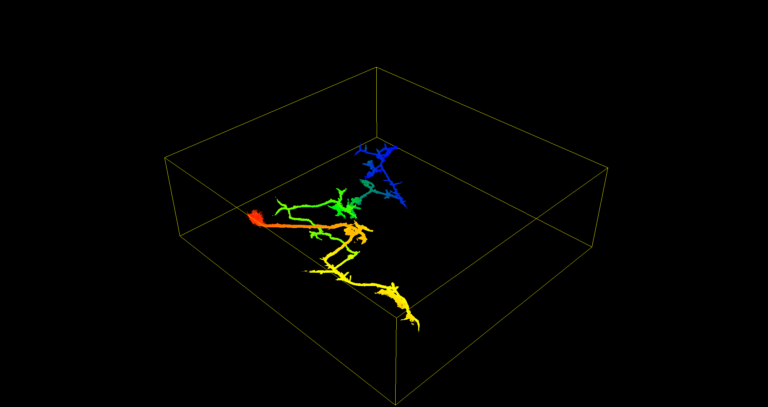

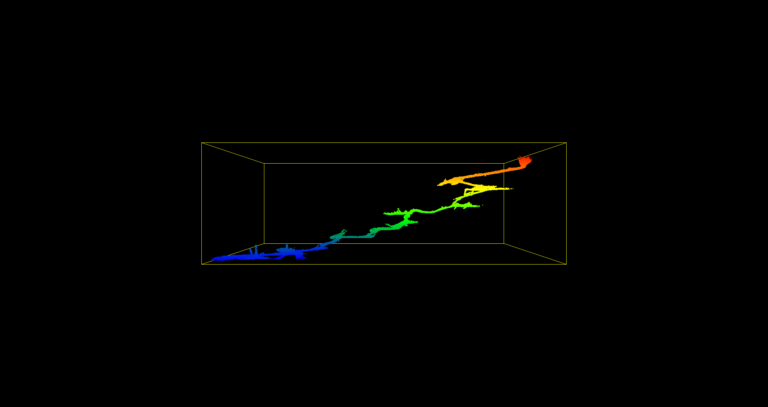

Our visit on the 24th of May 2020 was another productive day at Hilarion Mine. We pushed underwater further than we had ever been before reaching the end at a small shaft used to deposit the ore. Successful underwater mapping of Hilarion Mine was completed using the new tool designed by Stelios Stamatakis. After downloading the data from the VPlotter we produced a 2D top view map of the underwater passages. In total 126 meters where explored and mapped.

The 2D mapping in the field was carried out by Stelios Stamatakis, using the VPLOTTER surveying tool.

The above illustration was created by Errikos Kranidiotis.

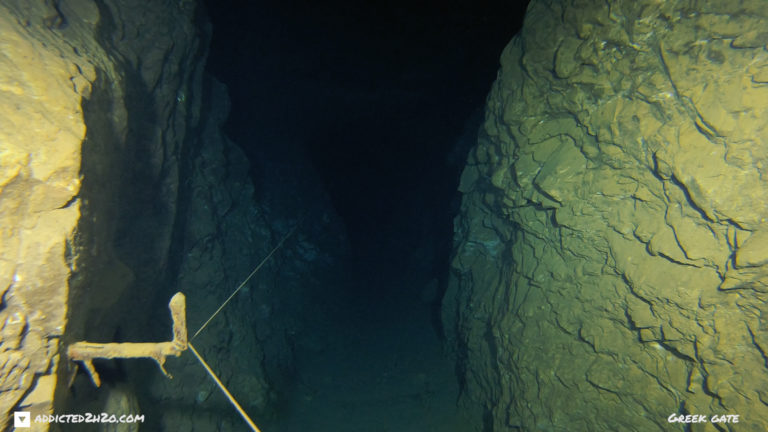

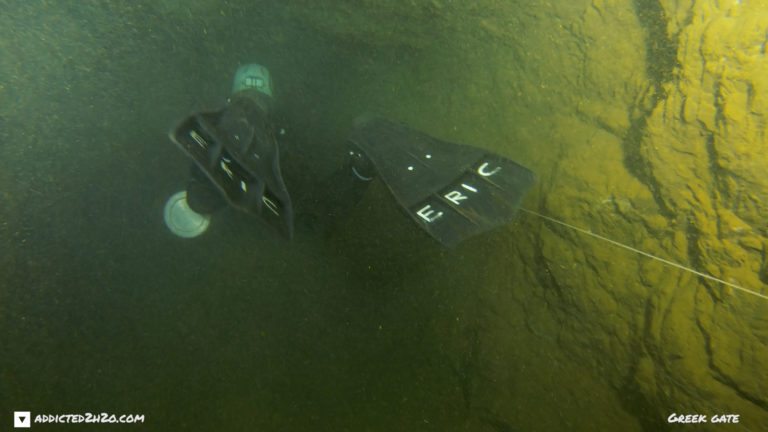

Underwater the mine continues its course, in a complex section of galleries, crafted by natural rock. Many of the galleries’ entrances have wooden columns, while remnants of rail tracks that lead to the heart of the mine are found. The divers through a series of dives managed to film unique images. The clarity and visibility of the water in the mine was amazing.

As evident by the video footage, the only difficulty underwater is safely returning back to the entrance. The divers encountered “percolation”, from the exhalation of bubbles and fin movement during entry. The fine particles cause loss of visibility in some parts right down to almost 100%. This is a normal and expected phenomenon in cave diving in limited spaces. The greatest difficulty was getting the divers and necessary equipment to the dive site, this took at least one and a half hour’s walk from the entrance of the mine. The fresh water measured a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius.

The divers stated: “Over time the original image of the mine has been distorted irreversibly and deprives current and future visitors the gathering of important information about its history. Possibly the water element is what has protected and preserved the image of the mine when the miners ceased their works. You feel at awe when you are underwater like you go back in history and can almost see faint images of the people who worked under such adverse conditions.”

A special thank you for the support from Xdeep, Landmark Loutridis and the team of people onsite without whom this would not be possible.

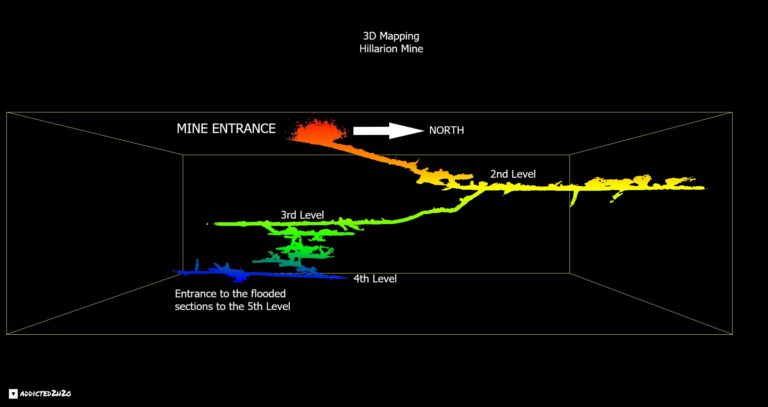

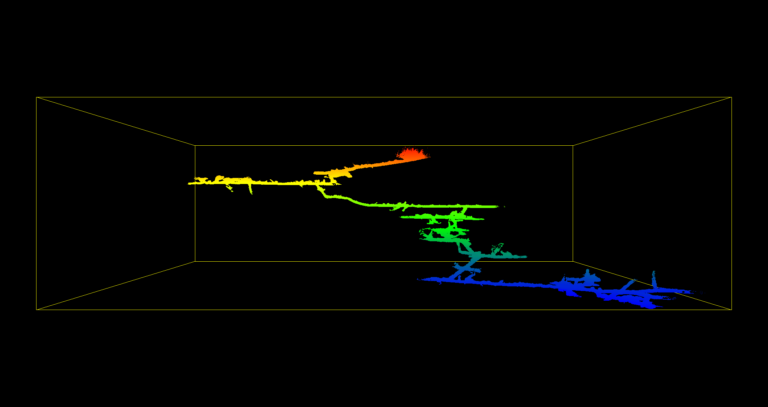

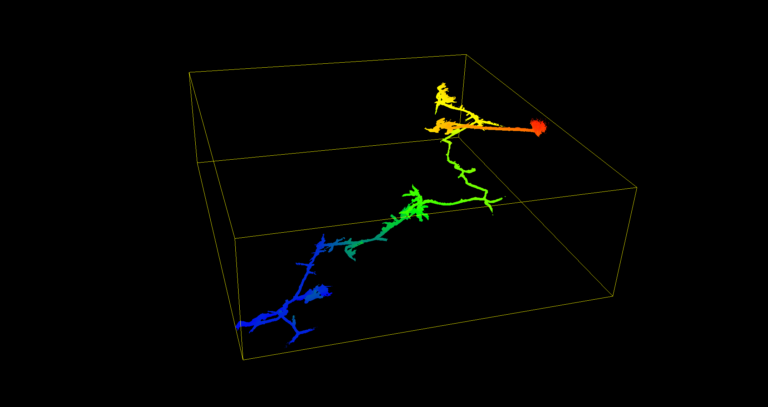

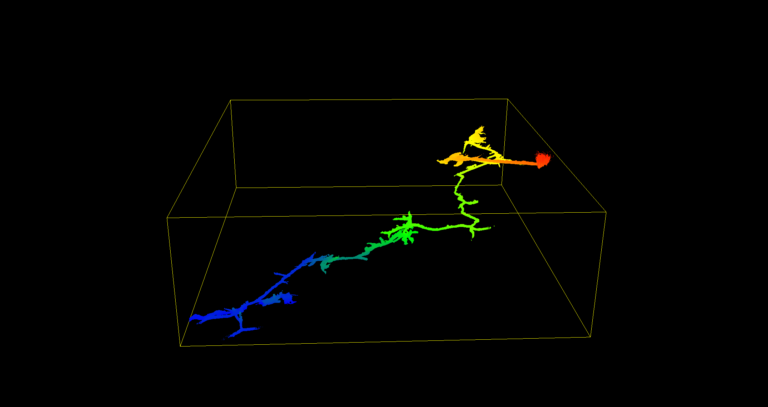

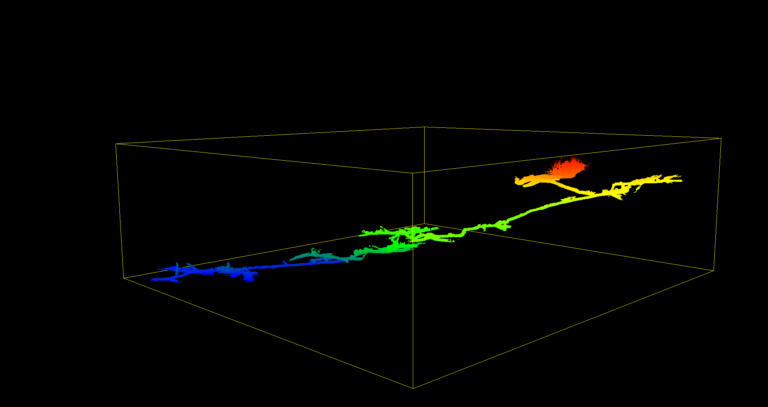

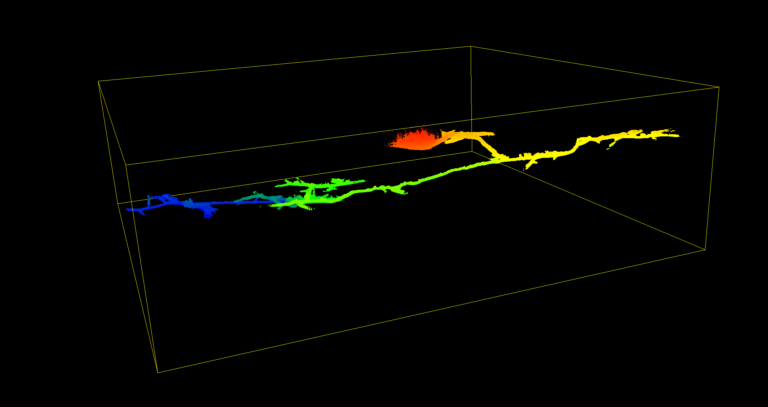

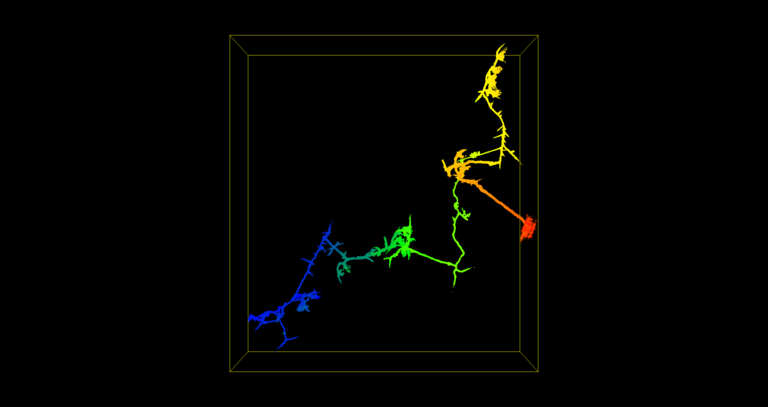

On the 25th of May 2020 the team visited the mine to conduct 3D mapping. The mapping in the field was carried out by the Surveying Engineer Yiannis Psaltakis and the company Landmark Loutridis. The video was edited by Erikos Kranidiotis.

VIDEO

3D Maps

The 3D mapping in the field was carried out by Yiannis Psaltakis, Surveyor Engineer and the company Landmark Loutridis.

The above illustrations were created with the Cloud Compare software by Errikos Kranidiotis.

The Teams:

Addicted2h2o: https://addicted2h2o.com

GreekGate: https://www.facebook.com/PyleEllenikonArchaiologikonIstorikonSpoudon/

Sources:

-Lavrio Historical-Technological Cultural Park (www.Itp.ntua.gr/home_en)

-The Archaeological Guide of Thorikos (Ministry of Culture)

-Athanasia Markoulis-Boudiotis, “Lavrion French Mining Company (LFMC): Its evolution and contribution to the development of the Greek economy during the 19th and 20th centuries”, Lavreotiki Development Association 2010.

Historical Research:

Mary Fotiadi

Photography:

Trifonas Egglezos

Mary Fotiadi

Support & Logistics:

Vasilis Stergiou

Apostolis Tzamalis

Akis Pallis

Georgia Manzi

Mary Zervakaki

Irini Zissimopoulou

Mary Fotiadi

Konstantinos Kalomiros

Kostas Efthimiadis

Kyriaki Foster

Alexandros Lykos

Graphic Design:

Maria-Louiza Karagiorgou

Greek Text Proofing:

Panagiotis Pletsas

Matlab Support:

Greg Moschonas

Dry section 3D Mapping:

Giannis Psaltakis

Mine Divers:

Erikos Kranidiotis

Stelios Stamatakis

Dive Dates:

20 July 2019, 19 November 2019, 24 May 2020.

Do what you can’t