German Submarine

U - 133

U-133 A Dive into Silent History

Just a few kilometers off the coast of Aegina Island, Greece, lies one of the most hauntingly beautiful wartime wrecks of the Mediterranean: the German submarine U-133. Resting silently at a depth of approximately 78 meters, this World War II U-boat is not only a challenging technical dive, but also a powerful time capsule that connects the present to the echoes of a turbulent past.

Our team at Addicted2H2O had the privilege of exploring this underwater grave, experiencing firsthand both the formidable conditions that define this dive site and the weight of the history it holds.

The History of U-133

U-133 was a Type VIIC U-boat, one of the most common and battle-tested German submarine classes used during WWII. Commissioned in 1941 under the command of Fregattenkapitän Hermann Hesse, U-133 was based out of the Axis-controlled naval facilities in Salamis, Greece. Despite its relatively short operational lifespan, U-133 was a formidable part of the Kriegsmarine’s Mediterranean fleet.

Tragically, on March 14, 1942, shortly after departing Salamis, U-133 struck a naval mine just southwest of Aegina. The mine was part of a defensive field laid by the Greek Navy prior to the German occupation — a type locally developed and referred to as a “Moraitis” mine, named after the Greek officer responsible for its design.

The explosion was devastating. It blew off the entire bow section of the submarine, causing U-133 to sink rapidly. All 45 crew members aboard perished. The wreck now rests with its bow separated from the rest of the hull, lying at a distinctive angle on the seabed.

The Dive: Conditions and Challenge

Diving the wreck of U-133 is not for the faint-hearted. At a depth nearing 80 meters, this is a deep technical dive, demanding precise planning, rigorous decompression schedules, and a high level of experience. Our dive took place under what appeared to be ideal surface conditions—clear skies, calm seas, and excellent visibility. However, the real challenge began once we descended.

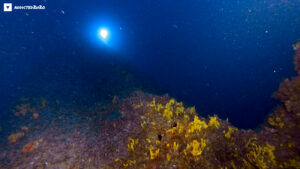

A powerful current ran down the shot line, stretching all the way to the seabed. Maintaining position on descent required tight control and teamwork. Descending through the deep blue, the shadow of the wreck slowly came into view—a ghostly silhouette resting in the silt, partially colonized by marine life but unmistakably human in its geometry.

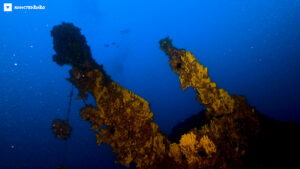

As we reached the site, we were immediately drawn to the point of impact—the very place where the Moraitis mine tore into the hull. The damage is still visible today: the entire forward section is absent, sheared cleanly away by the explosion resting under the stern of the submarine. Nearby, parts of the bow rest awkwardly in the sand, the angles speaking silently of violent motion arrested mid-collapse.

Encountering the Wreck

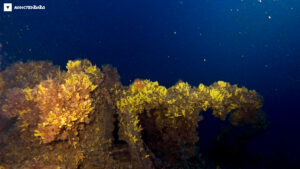

Swimming along the remaining hull, we noted the overall preservation of the structure. The pressure hull, conning tower, and torpedo loading hatches are still discernible. Corals and sponges have claimed parts of the wreck, creating surreal contrasts between rusted steel and bright life. In a strange way, the wreck now serves as both a war grave and a marine sanctuary.

We spent our precious bottom time capturing imagery, surveying the structure, and observing the subtle signs of decay and life taking root. The atmosphere at that depth is otherworldly—muted, still, and sacred. Every diver on our team moved with quiet reverence, knowing full well that we were exploring not just metal, but memory.

Reflections on War and Wrecks

Wreck diving is often seen as a thrill-seeking pursuit, but at its best, it is much more than that. Sites like U-133 force us to confront the real cost of conflict. Forty-five men went down with this vessel. Their remains likely still rest inside. No salvage operation was ever conducted, and the wreck is regarded as a war grave.

This makes the dive not just a technical achievement, but a solemn experience. The silence, the pressure, and the scale of the wreck make it feel like a moment frozen in time. It’s not hard to imagine the chaos of that day in 1942—the explosion, the darkness, the sudden flooding, and then the silence.

Diving here is a form of witnessing. As divers, we carry the responsibility to document and respect these sites, ensuring they are remembered, protected, and never trivialized.

Divers:

Erikos Kranidiotis

Stelios Stamatakis

Sources:

Research by Dimitris Galon: http://www.academia.edu/36894575/U-133

Information from the extensive research conducted on the shipwreck by Grafas Diving.

Technical Aspects and Safety

Dives on U-133 require trimix gases due to depth and narcosis potential. Our team followed strict gas management protocols, planned a multi-stage decompression profile, and use of closed circuit rebreathers. Total dive time exceeded 90 minutes, with a relatively short bottom time at the wreck itself. The dive profile was complex, but each step was executed with precision.

Visibility was excellent at the wreck site—ranging from 15 to 20 meters—which allowed for good photographic documentation and orientation. The strong current posed a challenge during both descent and ascent, requiring secure use of the shot line and staged decompression stops.

Because of its depth and the dynamic conditions, this dive is suitable only for experienced technical divers with proper certification and familiarity with deep wreck procedures. Proper training and respect for the environment are non-negotiable.

A Living Monument

The U-133 is not just a dive site. It is a monument, preserved by time and depth, telling the story of a violent moment in the history of naval warfare. It reminds us that the sea holds not only beauty, but memory—some of it buried beneath layers of silt and steel.

We will continue to document and share these stories through our platform, Addicted2H2O, hoping to inspire both appreciation and respect for the deep—and for the history that sleeps beneath its surface.

Do what you can’t